Marek Kwiek and Wojciech Roszka published a new paper in „Higher Education” (Open Access):

„Once highly productive, forever highly productive? Full professors’ research productivity from a longitudinal perspective”.

Kwiek, M., Roszka, W. Once highly productive, forever highly productive? Full professors’ research productivity from a longitudinal perspective. High Educ (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-023-01022-y

Link: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10734-023-01022-y, or here.

PDF is here.

Abstract:

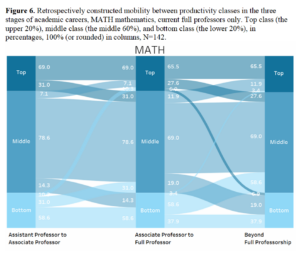

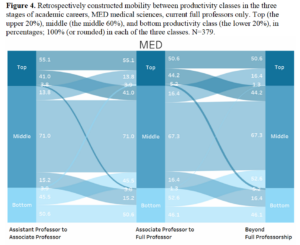

This longitudinal study explores persistence in research productivity at the individual level over academic lifetime: can highly productive scientists maintain relatively high levels of productivity. We examined academic careers of 2326 Polish full professors, including their lifetime biographical and publication histories. We studied their promotions and publications between promotions (79,027 articles) over a 40-year period across 14 science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and medicine (STEMM) disciplines. We used prestige-normalized productivity in which more weight is given to articles in high-impact than in low-impact journals, recognizing the highly stratified nature of academic science. Our results show that half of the top productive assistant professors continued as top productive associate professors, and half of the top productive associate professors continued as top productive full professors (52.6% and 50.8%). Top-to-bottom and bottom-to-top transitions in productivity classes occurred only marginally. In logistic regression models, two powerful predictors of belonging to the top productivity class for full professors were being highly productive as assistant professors and as associate professors (increasing the odds, on average, by 179% and 361%). Neither gender nor age (biological or academic) emerged as statistically significant. Our findings have important implications for hiring policies: hiring high- and low-productivity scientists may have long-standing consequences for institutions and national science systems as academic scientists usually remain in the system for decades. The Observatory of Polish Science (100,000 scientists, 380,000 publications) and Scopus metadata on 935,167 Polish articles were used, showing the power of combining biographical registry data with structured Big Data in academic profession studies.

(Excerpt) Introduction:

This study explores persistence in research productivity at the individual level over academic lifetime. We examine the trajectories of the academic careers of 2326 Polish full professors, including their lifetime biographical histories and their lifetime publication histories. We studied the dates of their academic promotions and their publication output (79,027 articles) between promotions over a 40-year period across 14 science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and medicine (STEMM) disciplines. Our focus was on transitions between productivity classes throughout the professors’ academic careers, from the assistant professor stage to the full professor stage.

We hypothesized that the current placement of full professors in the productivity classes of top, middle, and bottom (i.e., top 20%, middle 60%, and bottom 20% of scientists in prestige-normalized productivity in each discipline) corresponds, to some degree, to their placement in productivity classes at earlier stages of their careers. We speculated that current highly productive full professors could have also been highly productive associate professors and highly productive assistant professors earlier in their careers.

Our starting point was the current distribution of full professors by productivity classes in the 4-year period from 2014 to 2017. They were classified as either highly productive, average productive, or low productive. We then examined the productivity classes to which they could be retrospectively assigned at earlier stages of their careers.

The guiding thread of the paper follows the central findings of studies of highly productive scientists and their attributes (e.g., Fox & Nikivincze, 2021; Yin & Zhi, 2017; Agrawal et al., 2017; Cortés et al., 2016; Abramo et al., 2017; Kwiek 2016). Our research addresses three parallel questions: To what extent does scientists’ research productivity change over their academic lifetime? Have currently highly productive scientists always been highly productive? Is it rare for radical changes (moving up or down) in productivity class to occur over academic careers? Most productivity studies focus on the individual traits of highly productive scientists, and many combine individual and organizational (environmental) features (Fox & Mohapatra, 2007; Fox & Nikivincze, 2021). Our approach to productivity analysis is longitudinal, relative (class based), and prestige normalized:

- longitudinal: we trace the productivity of full professors in our sample for several decades (since they entered the higher education system)

- relative: we do not examine publication numbers but focus on productivity classes, retrospectively assigning individuals to classes and comparing scientists to their peers in their disciplines and career stages

- prestige normalized: more weight is given to articles in high-impact journals than to those in low-impact journals, recognizing the highly stratified nature of academic science, especially in STEMM disciplines

Beyond its scholarly implications (in theories of productivity), persistent high productivity over the course of individual scientists’ careers has implications for hiring and promotion policies. How can high productivity be maintained in departments, institutions, and national systems when, as this research shows, there is only marginal mobility between the lowest and highest productivity classes?

In this study, the unit of analysis was the individual researcher, not the individual publication. Although we used a combination of administrative, biographical, and bibliometric data, our research was not bibliometric in nature and belongs to academic profession studies. It was not possible to perform lifetime retrospective analyses of individual scientists without having full access to raw bibliometric metadata for all publications by all individual Polish scientists in the past 50 years. It was not possible to construct retrospective productivity classes for all scientists by discipline, career stage, and selected periods between promotions without having access to each scientist’s global publication metadata – without the ability to collect structured Big Data from Scopus, a commercial bibliometric database. Our study provides an example of combining structured Big Data and national registry data to conduct detailed analyses of academic careers within a national (i.e., Polish) academic science system.